[DATA IN THIS POST IS CONTINUOUSLY UPDATED ON **THIS PAGE**, PLEASE LINK TO IT INSTEAD OF THIS ONE.]

In Part 1, I distilled student debt bubble skeptics’ points (Annie Lowrey, the Economist, and Baum and McPherson) This post will conclude and add some research on student debt.

There are two problems I have with the skeptics’ thinking that haven’t come up yet.

1). If student debt isn’t a bubble, then what’s the solution?

The Economist says nothing. Baum and McPherson, who think student debt surpassing credit card debt is irrelevant, whistle Dixie past the problem, so they’re of no help. Lowrey’s attitude, though, is simply disturbing.

For better or worse, students cannot discharge college loans through bankruptcy.

Anyone with common sense should conclude that the undue hardship exception is a terrible idea on both economic and moral grounds. The only people who could counsel maintaining a lopsided system that allows banks to take on zero risk are banks and universities. It is indefensible.

My solution for student debt: cancel all government guarantees, return all consumer bankruptcy protections, and any banks that fail get nationalized by the government, which then wipes out their bad assets, breaks them up, resells them to the public, insures the depositors, and convicts anyone who committed fraud.

But wait, that’s the same solution I’d give to anyone asking me about the solution to the housing bubble, or the Japanese real estate bubble, or the Great Depression. If it looks like the housing bubble, and the solution’s the same, then why is student debt not a bubble? The remaining questions are how big is it, and what’s its effect on the economy?

2). Student debt is inhibiting economic recovery.

Anyone who knows anything about the American economy will tell you that after the housing bubble burst, households began paying down outstanding debt. The problem is that when everyone does this simultaneously, you get two things you don’t want: (1) nonexistent growth, for growth = spending = income, and (2) disinflation because in principle every loan issued is inflationary while every loan paid off is deflationary. These two factors both contribute to high unemployment. In short: a depression.

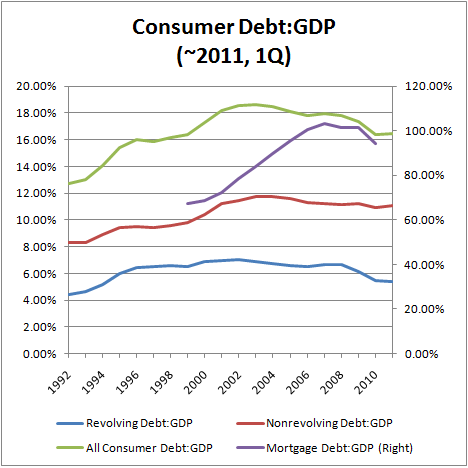

Take a look at this graph of three components of household debt: mortgage debt, revolving debt, and nonrevolving debt (which includes student loans).

You can see the severity of the mortgage bubble and the ongoing market correction. You can also see that nonrevolving debt is still growing while the others aren’t.

When we discuss debt, we should expect it to always be at a nominal record high since output is also usually at a nominal record high, so to see where we’re at, here’re the debts as a ratio of GDP:

(Sources: GDP (BEA), Nonrevolving, Revolving, and Total Consumer Debt (Federal Reserve, G.19 Release), Mortgage Debt (Federal Reserve, 1.54 Release (2009-2011, archives 2004-2008 (the February updates show the data from five years earlier)); note that the last data point is the 1st quarter 2011 (annualized), so the graphs are slightly distorted but project 2011’s trend)

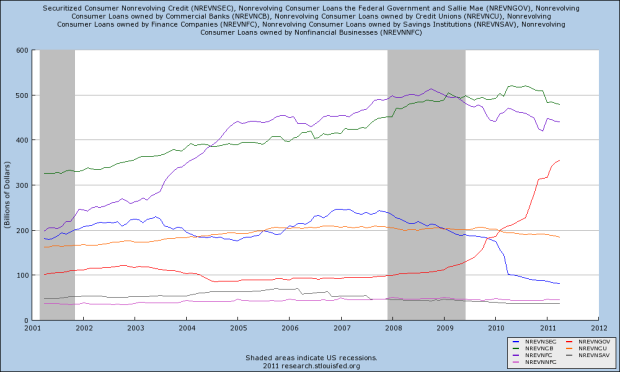

Notice how in 2007-2008 all debts start deleveraging while nonrevolving debt does not? While we don’t know the exact amount of student debt, we do know who owns it, courtesy of FRED.

Your first thought might be, “Holy shit! Look at how much nonrevolving debt Uncle Sam picked up since 2009!” Ah, but according to the Fed, much of that’s actually attributable to a change in accounting rules:

The shift of consumer credit from pools of securitized assets to other categories is largely due to financial institutions’ implementation of the FAS 166/167 accounting rules.

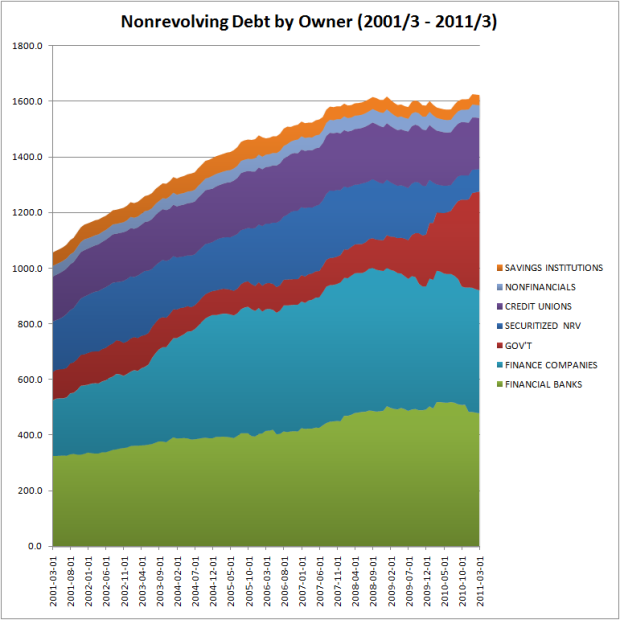

By “other categories,” the Fed means the federal government. More subtly, the government category included Sallie Mae until it was privatized in 2004, hence the bulge in “Finance Companies” back then. Here’s the same data in a stacked chart:

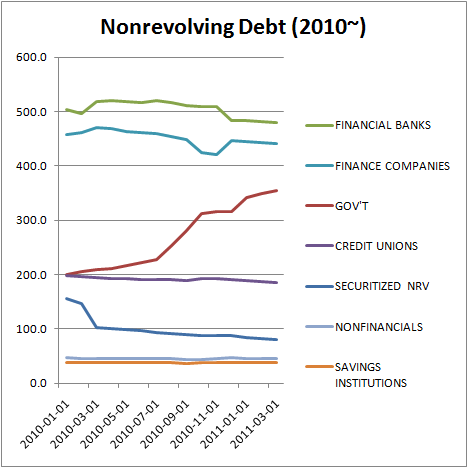

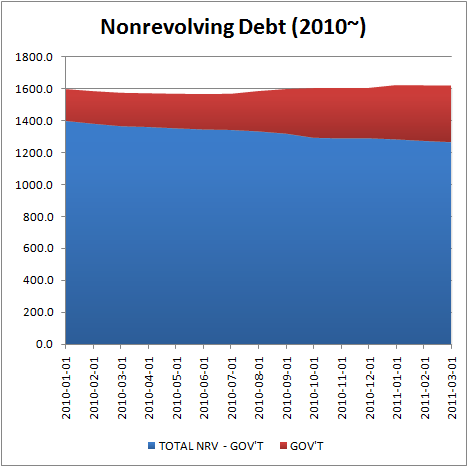

The new accounting rules went into effect by January 2010, but even then, the federal government is the only owner of nonrevolving debt whose holdings are growing. Most of the $150 billion in the last year and a quarter are likely student debt (unless the government is buying up home equity lines of credit (HELOC) as part of the Fannie/Freddie takeover, which I doubt). Please gaze.

The Federal Reserve released its quarterly G.19 Release a few weeks ago. By the end of March 2011, nonrevolving debt grew at a 5.6% annualized rate, which is bad enough, but the government’s share grew at an annualized—I kid you not—58.8%, from $316.4 billion to $355.2 billion (or 19.7% to 21.8% of total nonrevolving debt; 2.16% to 2.41% debt-to-GDP). That’s in just one quarter!! Revolving debt continued dropping, except in March. Meanwhile, the bad news is that GDP only grew 1.8% first quarter.

Government holdings of what are likely student loans aren’t taking over the financial system, but their rapid expansion against a depressed economy is very bad. I emphasize that the remaining student debt is held privately, though the quantities are jumbled with the other kinds of debt they own (HELOCs, vacation loans, auto loans, etc.). We only know that their aggregate holdings are decreasing, for now.

I can’t imagine any instances when debt growing faster than output is good, aside from some kind of significant long-term investment that doesn’t pay off in the short run, which we know isn’t the case here. The bubble skeptics don’t see these problems. I will watch what they say as growth stagnates and student debt and resistance increase.