Reading Karen Sloan’s National Law Journal piece “Tuition Is Still Growing” and all the commentary it’s spawned reminded me of what happens when you go to a store on November 1st: the remaining Halloween candy, costumes, and decorations are dirt cheap because the store has to get rid of the undemanded surplus to make room for Thanksgiving and Christmas items. The appeal to “Supply and Demand 101” surrounding tuition increases makes the same assumption: There’s been a drop in applications, so why isn’t there a corresponding drop in prices?? The answer should be obvious by now: the market for law degrees is not a “101” market. If it were, I wouldn’t’ve called it a tuition bubble for the last two years. Here are 10 reasons why there is no cause for surprise.

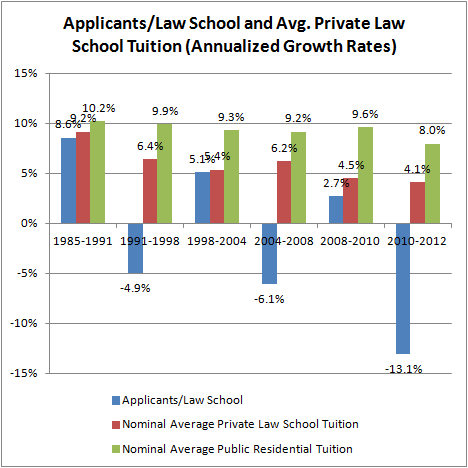

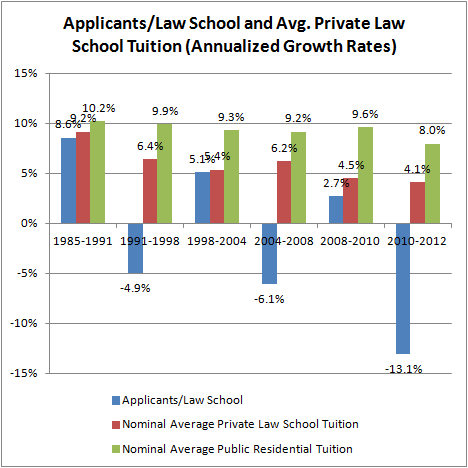

(1) Past application drops haven’t correlated to tuition drops.

2011 and beyond is not the first time law schools have seen a drop in applications and raised tuition nonetheless.

To make this more intelligible, here’re the annualized growth rates from trough to peak and peak to trough over the years.

Thus we shouldn’t be surprised tuition always goes up, though we should acknowledge that the current growth is smaller than previous applicant dips. For it’s worth I would’ve predicted average private tuition would’ve gone up by less this year, like 0.8 percent over inflation rather than 1.7 percent.

(2) Law school applicants are transient, one-time-only, pass-through buyers.

None of the blather about how tuition is driven by students’ demand for “services,” posh buildings, etc. ever addresses this particular asymmetry. Applicants do not fully inform themselves of the market in one application cycle and then wait for the November 1st of legal education to buy discount law degrees—and don’t waste my time showing me 1Ls who bargained large scholarships out of their law schools this year. None of them were sitting around reading Big Debt, Small Law in 2008 thinking, “I’ll bide my time for four years living paycheck to paycheck and apply in 2012 when applications nosedive!” In other words, the decision to apply is much more significant than where to apply and how much to spend. No one who chose not to apply to law school, because they thought it was too expensive, has ever waited for the price to drop. Those who have chosen not to apply are never coming back.

(3) Applicants suffer from crippling information asymmetries, and any decent information they do get will largely discourage them from applying.

I seriously doubt any potential applicants who look on Law School Transparency’s Web site or comb the ABA data for themselves are going to apply to an underperforming law school before giving up altogether and trying for med school instead. Any price comparisons they conduct will largely come from U.S. News‘s rankings, which are released every February. Even then, as I discovered when going through law schools’ Web sites two years ago, law schools set their fall tuition after students have signed up to buy the degree, so students don’t really know how much they’ll be paying until they show up for orientation. If they’re really unlucky the tuition will be published in credits per hour, which makes comparisons even more difficult. This is not “101” price signaling.

But it gets worse. Law schools’ Web sites also proclaim that they reserve the right to revise their tuition rates without notice. Then they list numerous, unexplained fees, such as the “academic excellence fee,” and less mysterious ones like the “library technologies fee.” Nonetheless, potential applicants have no idea whether these fees are allocated to the library or “academic excellence,” or what happens if there’s a shortfall or surplus to either. Indeed, it would be very simple for a law school to simply shift more of its costs into nonsense fees and then claim it’s holding tuition steady. Applicants who check the Web sites alone wouldn’t know any better, which is why they’re forced to wait for U.S. News to tell them how much they would’ve paid if they’d applied the previous year.

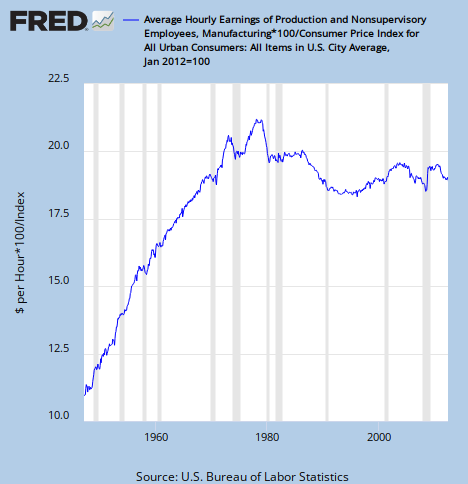

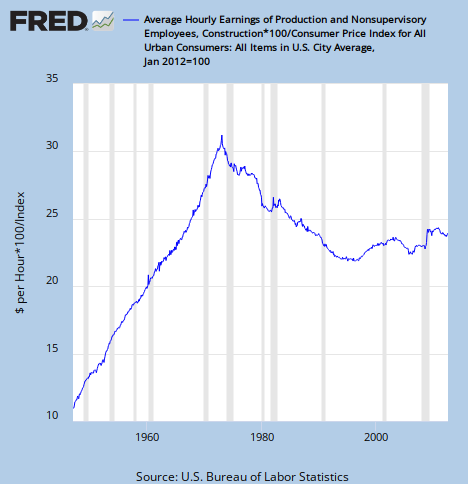

(4) Those of us who’ve been reading Krugman have learned that while “Supply and Demand 101” says one thing, empirical facts say that nominal wages and prices tend to be “sticky downwards.”

Nominal prices frequently do not drop much absent a serious crisis, even the November 1st example above isn’t perfect in this respect. Law schools are more likely to freeze hiring, freeze salaries, lay off (non-tenured) employees, or freeze tuition and let inflation eat at it before announcing a 30 percent nominal cut to attract applicants. Indeed, in 2011, only two private law schools reduced their nominal tuition over the previous year (University of Dayton and University of St. Thomas (MN)), Ave Maria held it constant, and another 19’s nominal increases were engulfed by inflation. Generally, nominal tuition growth has been slowing, but that’s the limit of what’s going to happen:

5.7% is the average nominal tuition increase for this period. The average deviation is 1.75%.

(5) The disadvantages the buyers have also cut against law schools that want to signal price drops.

If a law school wanted to cut tuition to attract applicants, in the first place it would have to predict that it would get fewer paying matriculants during the next application cycle, announce it was planning to drop tuition the next year, somehow convey that to potential applicants (outside of U.S. News), hope that current students wouldn’t take a leave of absence to capitalize on the anticipated price drop, and hope the applicants don’t see it as a sign that the school is about to cut prices again, lose prestige, or fail and then still apply. The problem is, once students promise to show up, the law school has to choose to (a) cut tuition as promised, or (b) raise tuition because there’s “demand” for its degree, “services,” new buildings, etc.

(6) Law students don’t set price ceilings and walk away if the law school raises costs ‘too high.’

If a law school sees a severe enough crunch in matriculants that affects its operating budget, it can simply raise tuition to cover the shortfall, as Cooley did this year. Why? Because the entering students don’t actually look at the tuition increase that occurs between when they apply and when they get their first bills, if it’s even announced. Between tuition and, especially, unknown living expenses, students have already committed to paying a lot of money, as much as the law school told them to pay. It’s like buying something at the grocery store and looking over the receipt when you get home and finding that they charged you more for an item than was on the price tag. Sure, you could’ve checked when you were at the register, but it’s not a big enough deal for you to care, and it’s not like you expected the store to charge you more when you weren’t looking.

Remember also that the consumer protection argument this phenomenon entails isn’t swaying too many judges to think that purchasers of legal education aren’t reasonably prudent consumers acting reasonably, even though the media still wonder whether it’s reasonable for purchasers to commit to buying a product before knowing the total cost and without knowing that the seller regularly raises prices at will.

As for current students, they’re hosed—not that they look at their tuition bills either. They too have capitulated and will pay whatever the law school feels like charging them, and it’s not as though they’ll transfer to cheaper schools, drop out, or protest in response, which leads to…

(7) Exit, voice, or loyalty?

One of the hopes I’ve had over the last two years is to see law students wake up to tuition increases. That’s why my blog’s title is about tuition and why I’m painstakingly revising a page that lists every law school’s tuition increases, though I’ve long since expanded beyond the topic. The truth is, law students are willing to shoulder significant tuition increases without any protest. If Albert O. Hirschman’s book Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States were applied to law students, they choose loyalty over exit and voice.

While the closest thing to law school protests I can think of were at the University of Virginia a few years ago by some 3Ls who were talked out of attending a 0L function wearing t-shirts describing how much debt they had with no jobs, the only serious example of university students choosing voice that I can think of weren’t law students but were the campus Occupiers last year, mostly at California’s public universities. It’s telling that they were almost exclusively public university students, and they perceived the states’ decisions to cut the subsidies to their universities as abandoning an important, job-creating public institution. They weren’t concerned about spending on frivolous outlays like climbing walls, and they certainly weren’t going to ask whether jobs could be created without sending everyone to residential colleges. The protesters actually appear slightly conservative, not that the six-figure salaried Lt. Pike thought that while he was pitilessly pepper-spraying non-threatening protesters. The same sentiment goes for law schools: No one is demanding spending cuts, except those who aren’t applying, and they’re not going to come back when “November 1st” comes around.

For example, when Faulkner University increased its tuition by 43.1 percent over inflation in 2007, 22.8 percent in 2008, and 10.1 percent in 2009? No protest. New England School of Law increased its tuition by more than 15 percent two years in a row. Again, no protest. UC-Irvine might be a public-in-name-only law school whose students know that they’ll never receive any state subsidies, and its resident students paid $43,000 last year and don’t care.

Things are different today, and maybe the Faulkners and New Englands probably couldn’t get away with doubling their tuitions if they wanted to, but since law students don’t set price ceilings on how much they’re willing to pay, and given that they (wrongly believe they) are powerless once they enroll, they don’t have many options. They can drop out (exit), or they can demand transparent employment data, though that doesn’t address their personal circumstances so isn’t much of a voice.

But they won’t organize, and the students who are cunning enough to do so aren’t applying anymore. I fear that law students have lost their chance for self-help. From now on law schools will be admitting a combination of people savvy enough to play the scholarship game and people law schools know aren’t reasonable consumers, whether judges think they are or not.

(8) Law schools have bondholders.

Unlike their graduates, law schools have some options for paying back the money they owe to their lenders. They are also allowed to file bankruptcy. Rest assured, law schools, particularly the free-standing ones, that are under their creditors’ thumbs are not going to announce large revenue cuts. For the free-standers, large tuition retrenching is more likely to occur after a Chapter 11 filing, and schools attached to universities are more likely to just be shut down by their central administrations once they realize that it’s not profitable anymore.

(9) Speaking of which, most law schools take their orders from central universities that have their own priorities, e.g. profiting from law students.

Remember what happened to the former dean of the University of Baltimore Law School, Philip Closius, when he told the ABA that the university was hauling away 45 percent of the law students’ tuition and state subsidies for non-law school purposes? Central administrators know that students will pay what they ask, and when it’s no longer worthwhile, they’ll just close the program.

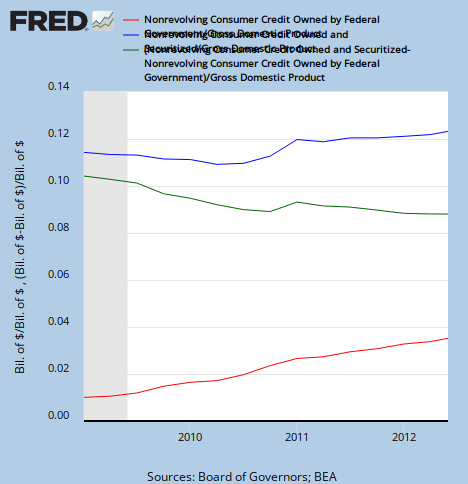

(10) Law students are publically subsidized.

The NLJ article mentioned this, but it alone should tell us that we’re not in a “101” market, but it had to be said.

*****

From now on, do not be surprised that average law school tuition is increasing even though applicants are not. It would take an unusual set of circumstances for any one law school to voluntarily cut its tuition and still expect to survive.