Ten years after the Iraq invasion, the paper of record is finally catching on.

For some reason the link doesn’t work, so I’m just going to quote the article in full. I’m sure the Times won’t mind.

If anyone could teach a course in how to remain calm with sovereign debt, it’s Jack Lew. Managing the finances of a declining superpower with a net public debt-to-GDP ratio of 73 percent, a rent-seeking health care system, low taxes on the rich, high youth unemployment, and endless wars takes equanimity. Lew tells me over a latte, “The trick is to ignore all the naysayers claiming that we’re in a depression and willingly believe in America’s dynamism.” His creditors would foreclose on him, except he didn’t spend the money on a house but on foreign occupations. By all metrics, it’s been a catastrophic investment, except for one: the United States military.

Looking at the statistics that the U.S. military gathers and provides to U.S. News & World Report to publish in its influential rankings, invading foreign countries for any reason or no reason seems like a great investment, with an average of one corner about to be turned every three months since the magazine began tracking “success after invasion” data in 2001.

How can the military paint such a rosy picture to U.S. News?

“It’s an open secret that the American public has no idea what the military is doing in Afghanistan or Iraq,” says U.S. Army Colonel William Hendricks, one of many exasperated officers cajoling the Department of Defense to change how occupation forces are assessed. “We need to come up with a way for armed conflict consumers to know when they’re getting the Army of the Tennessee under Grant and Sherman or the U.S. Army under Westmoreland and Abrams in Vietnam.”

For example, a corner is claimed to about to be turned whenever a Predator drone kills thirty revelers at an Afghan wedding party, which the military then claims were Taliban fighters all along. Corners are also neared for every hundred Afghanis who enlist for training by the U.S. military, but it won’t tell you that they then promptly desert, taking their bonuses with them. Simply sending more soldiers to the country (called “surges”) also helps it approach corner-turning—and gives the military more money.

The lack of any real corners being turned is enraging taxpayers, who are taking their protests to the Internet with blogs titled, But I Done Killed Everything Right!, Rose Colored WMD, Restoring Dignity to the Death Squad, and Killing Them Die Hard. “Stay clear of this disgusting, putrid, shit-pile of filth called the U.S. military if you want economic growth,” writes the author of the blog, THIRD TIER OCCUPATION—in typical scatological tone. “Unless, of course, you think adding $1 trillion dollars to your NON-REPUTIATABLE sovereign debt is worth no greater security and a reduced standard of living for your populace.”

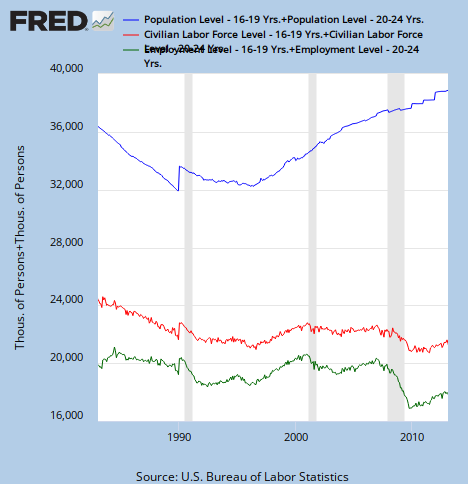

Sadly, there’s no shortage of citizenries willing to fork over trillions of dollars a year even though their economies haven’t produced enough jobs to keep up with population growth.

In February 2013 Congress subpoenaed the top brass to testify before a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing to hear their views.

“Militaries find it’s more cost-effective to simply pay out a million dollars per soldier per year than recommend Congress reinstitute the draft. The problem with non-volunteers is that they require more training and then frag their commanding officers when ordered to patrol Helmand Province. Occupying countries for no good reason is difficult, and that costs money,” testified recently promoted Brigadier General Irwin Chemicalinsky.

Responding to the beating the U.S. military has received as an investment from antiwar scambloggers, one general, Richard Balthazar said, “There’s this persistent myth out there that armed forces and weapons manufacturers are tricking Americans into invading and occupying other countries. That would make us immoral, unethical, and terrible people, and we’re not. Citizens must do their own due diligence before deciding whether to invest in foreign invasion as well as which military to use. There are plenty of popular security-debunking websites for them to read, so they’re informed by them rather than by our about-to-turn-another-corner numbers from last year. When the Treasury Department auctions those securities, they’ve made their choice.”

When asked by Committee Chairman Carl Levin (D-MI) if the military was committing waste, fraud and abuse of government funds, General Balthazar told Congress that the military is overcharging taxpayers for its services, primarily because it’s “grossly inefficient.” “Does the U.S. really need seventeen intelligence agencies, all of which are politicized? Probably not for America’s purposes. Would it be cheaper to send in commandos than fight a robot war in Pakistan? Sure. Do we need a Department of Homeland Security when we already have a Department of Defense? Yeah, that’s probably redundant too. Should soldiers do their own laundry instead of contracting it to KBR for no-bid contracts? I guess that’d be cheaper. But it’s not like the brass has some moral obligation to tell the American public that spending $100 billion per year occupying a Central Asian un-state is a waste of the United States’ non-repudiatable debt dollars. A little caveat emptor here, people.”

Another officer suggested that U.S. military unbundle its services, a “Motel 6” force for humanitarian missions or patrolling the Alaska-Canada border, and a “Ritz-Carlton” military of nuclear submarines and ICBMs for deterring Soviet invasions of West Germany.

Leaders of occupied countries quickly claim that American soldiers simply aren’t ready to forcibly control their territories upon arrival. Said Hamid Karzi, President of Afghanistan, “I don’t care what the rankings say, Americans simply suck at foreign occupation. The guys they’re sending aren’t nearly as good as the Brits were. I mean, they sent motherfuckers like Francis Edward Younghusband to Tibet. Why don’t the Americans have guys like him? He knew how to massacre monks. Hell, even the Soviets were better. Shit, they may not’ve turned any corners either, but have you seen the number of landmines they left in our country? Tons, man. Tons.”

When confronted with its “gross inefficiencies” the Department of Defense claimed that its hands were tied. “If we limit how military forces operate, we open ourselves to antitrust lawsuits,” incoming Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel commented, “Militaries worldwide need to find ways to cut costs, like sharing their aircraft carriers and nuclear arsenals.” He added, “We’re overhauling our military accreditation standards so that every armed force must declare what kind of wars it intends to be useful for, and we’re also going to ask militaries to voluntarily provide us with better about-to-turn-corner data.” In the meantime, Defense officials said they intend to negotiate with U.S. News as to how it ranks militaries. However, the magazine quickly pointed out that it won’t ask for any more corner-turning from the world’s armed forces unless the Defense Department comes up with better metrics first.

Asked about his concerns about his country’s sinking fortunes, Lew moped, “Hey, this is the age of bailouts. I’m sure someone will give us a grant. Or we could just double-down and go to law school.”

Again, no new surprises, and we shouldn’t expect any for the rest of the cycle, but these 54,000-56,000 or so applicants are much less likely to be the kind of post-college-aged folk whom law schools once thrived upon. I’m further willing to bet that the share of applicants to full-time programs is at a super low, and only a minority—an important minority, mind you—will be paying full tuition.

Again, no new surprises, and we shouldn’t expect any for the rest of the cycle, but these 54,000-56,000 or so applicants are much less likely to be the kind of post-college-aged folk whom law schools once thrived upon. I’m further willing to bet that the share of applicants to full-time programs is at a super low, and only a minority—an important minority, mind you—will be paying full tuition.