Oh Yomiuri Shimbun, why must you blight the Internet with such nonsense in your editorials on legal education?

[T]he number of lawyers employed by local governments and business corporations has not increased as much as anticipated. A large number of people are unable to find jobs after passing the bar exam.

…

Some law schools have been increasingly inclined to withdraw from their field of education in recent months. The move has accelerated since last autumn, when the education ministry said it would curtail grants-in-aid to law schools whose graduates perform poorly on the bar exam.

There was a time when law schools bloomed, with their number peaking at 74. But the number of law schools accepting applications for admission next spring is expected to decrease to 54. It is only natural for law schools to quit if their students do badly on the exam.

Clearly Japan’s law schools’ mistakes aren’t emulating the U.S. system but not emulating it enough. Employing the strategies used by U.S. law schools could really make a difference at these institutions because over here, we’ve internalized the following lessons. When graduates don’t pass the bar or don’t find jobs, do the following:

(1) Capture the accreditation system and calibrate it so that if graduates from all schools fail the exam at about the same rate, the schools keep their accreditation. You’re not over-enrolled if you’re just average.

(2) Blame the magazine rankings. (Don’t worry if they blame you back, you both make your money on the (prospective) applicants. It’s just part of the business.)

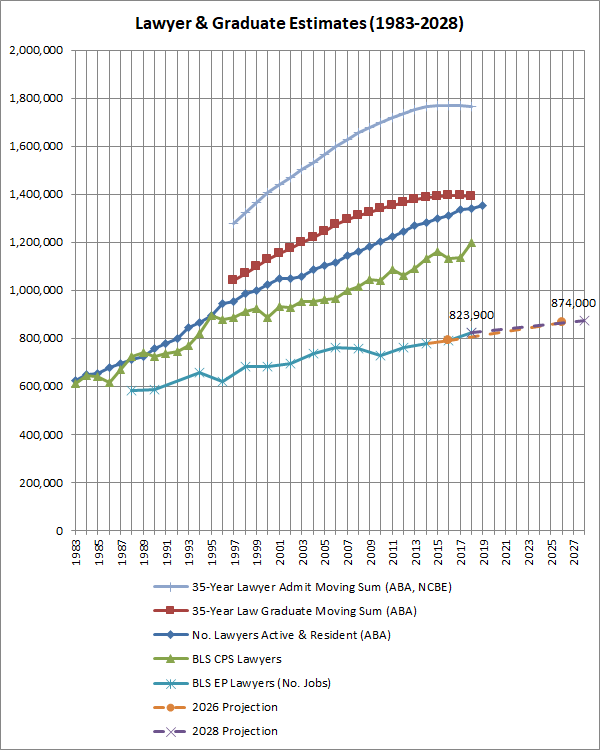

(3) Shake down your alumni to finance a new, gratuitous, state-of-the-art law school building. That’ll show ’em.

(4) Blame your graduates for being greedy, entitled, and unwilling to make the tough sacrifices, like opening practices in rural areas. Lots of people in Shikoku need lawyers.

(5) Alternatively, blame your graduates for moving too far from the school and trying to make money where the jobs are, like Osaka perhaps. After all, it’s not the school’s fault for enrolling too many students for the local market; rather it’s the students’ fault for wandering too far from where their degrees have any signaling value.

(6) Advertize your school’s discounted tuition thanks to senior students who are asked to pay full freight courtesy of unlimited government loans. (Japan has those, right?)

(7) Complain that the press and the blogs don’t use any facts—because they don’t.

(8) Use Pyrrhonian skepticism to dismiss government employment projections showing that there is no need for your graduates’ professional labor.

(9) Notwithstanding (8), point to the imminent wave of retiring lawyers whose positions will need to be filled.

(10) In case Abenomics fails, waive away any predicted productivity increases in legal services, low household incomes and formation rates, the apparent income elasticity of demand for legal services, and predictions that the economy is going to stagnate for many years to come. Do not waver: The backlog of graduates will clear!

(11) Claim that your graduates are easily finding jobs after the employment data are collected. Disregard the findings of longitudinal studies like After the JD in the U.S., which found that graduates who enter the profession in good years frequently leave law practice several years later due to massive attrition.

(12) Throw out marginal product theory, the law of diminishing marginal returns, and the sheepskin effect and argue that your school’s degrees are “versatile,” ensuring that graduates will get an earnings premium in any occupation besides law practice because all schooling increases earnings for all positions regardless of the skill required.

(13) Ask rhetorically, “What else will intelligent young people do?” Obviously law is the answer.

(14) Plead that your school is virtuous because it enrolls minority students who do poorly on exams. It doesn’t matter if they never enter the profession or can’t service their debts. (They have IBR in Japan, right?)

(15) Use the crash in applicants to encourage people to apply. After all, it’s not like everyone will seriously heed this advice and make it self-defeating.

(16) U.S. law schools haven’t tried this yet, but yous should: Insist that the profession’s licensing rules are so restrictive that they prop up prices for lawyers’ services, which is why so many of the highest earners in the country are lawyers. Therefore, anyone who graduates from your law school is a lucky ducky. If anything, the country should allow foreign-trained lawyers to practice as it will drive costs down.

(17) And if all else fails, compare the number of attorneys per capita in your country or region to others because that’s an obvious measure of lawyer shortages. Duh.

So Yomiuri Shimbun and all Japanese law schools, the problem wasn’t adopting the American model; it’s not adopting it all the way.