…Because really, who would authorize a guide on state bar reports?

As of last week, we now have at least four state bar association task forces/special committees/working groups/whatever offering their opinions on what’s wrong with legal education, law school debt, lawyer licensing, and the legal profession. Here is a list of the reports and links to my posts on them:

The two biggest themes, as far as I’m concerned, are what the task forces/committees/working groups/etc. thought about (1) student loan debt, specifically whether it’s passed onto clients and whether it should be dischargeable in bankruptcy, and (2) revising legal education and law licensing requirements to include more skills training over theory-heavy classes and whether that will result in better employment opportunities for new lawyers.

The NYSBA Task Force’s report didn’t say that student loan debt is passed onto clients, and it even chided lawyers who claim they want practice-ready law graduates but hire from elite law schools anyway. Most of the Task Force’s recommendations were tentative, but they did include changing licensing requirements to include assessing professional skills, adding a sequential licensing system, and adopting the Uniform Bar Exam. Instead, they got mandatory pro bono requirements. The quality in reasoning in subsequent state bars’ reports goes downhill from here.

Massachusetts’ Task Force determined—okay that’s being generous, it really assumed the conclusion—that poor training causes new lawyer underemployment because medical and dental schools require a lot of skills training and their graduates aren’t underemployed. Its report neglected to mention that those professions thrive with practitioner shortages or that aging boomers will need regular medical checkups. The Task Force said very little on student loan debt, and it advised transforming the third year of law school into a residency-type experience ala medical and dental school.

The Illinois Special Committee claimed that salaries for new lawyers are too low to support their student debts, public interest employers have difficulty paying new lawyers enough to cover their debts and suffer high turnover, and underpaid lawyers don’t serve the poor or “middle class” in favor of higher-paying lawyer positions or leaving law practice altogether. The Special Committee also believed that lack of practice-readiness also contributed to underemployment. Its recommendations on reforming federal student lending, however, were fairly reasonable.

Finally, California’s Task Force subtly concurred with the Illinois Special Committee’s reasoning on student loan debt, but it leaned more heavily on the practice-readiness problem by claiming that firms unfairly pass their new lawyers’ training costs onto clients. Better training would make new lawyers more productive (raising their incomes to repay their student loans) and simultaneously reduce costs to clients (I’ll discuss this nonsense later). The Task Force recommended requiring more skills courses and pro bono work of law students and new lawyers. This report is easily the most poorly thought-out of the four.

Law School Debt

Contrary to what I may have implied last week, none of the state bars’ reports explicitly say that law school debt is directly passed onto clients. However, the Illinois Special Committee report effectively makes that argument with its gathered testimony as listed in its executive summary (1-2):

- Small Law Firms Face Challenges Hiring and Retaining Competent Attorneys

“Many small law firms are unable to pay the salaries new attorneys need to manage their debt. As a result, turnover at such firms is high, forcing those firms to spend additional time and resources training new attorneys (compounded by the problem of inadequate readiness for practice upon graduation).”

- Fewer Lawyers are Able to Work in Public Interest Positions

“Attorneys with excessive debt are less able to take legal aid or government jobs which, in Illinois, have starting salaries between $40,000 and $50,000 per year. Public interest offices that raise their salaries to accommodate debt and attract talented lawyers are unable to hire as many attorneys, reducing the services these offices can provide.”

- New Attorneys Have Too Much Debt to Provide Affordable Legal Services to Poor and Middle Class Families and Individuals

“Salaries among law firms primarily serving the legal needs of middle class individuals and families are also inadequate to support the debt loads of new attorneys. … Because debt makes it difficult for attorneys to survive at that salary level, young attorneys move quickly to higher paying legal sectors if possible, and, if not, many leave the profession.”

- As Fewer Attorneys Find Sustainable Jobs in the Private Sector, More Attorneys Enter Solo Practice

[Note: This contradicts the first point on small practices being unable to hire lawyers. It’s a lot cheaper to work for a small firm than start a small practice.]

- Attorneys Report that Debt Burdened Lawyers are Less Likely to Engage in Pro Bono Work

- Debt Drives Young Attorneys Away from Rural Areas

“Already, rural areas of Illinois have significantly fewer lawyers per capita than more populated areas, because it is more difficult for lawyers to service significant debt in rural areas.”

[Oh God, don’t abuse attorneys per capita again…]

- Heavy Debt Burdens Decrease the Diversity of the Legal Profession

[Because there’s nothing minorities need more than low-paying legal work.]

- Threats to Professionalism

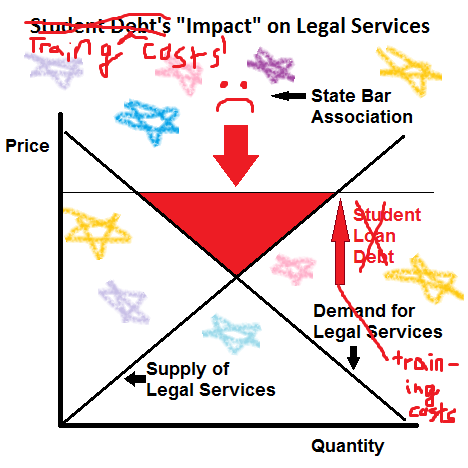

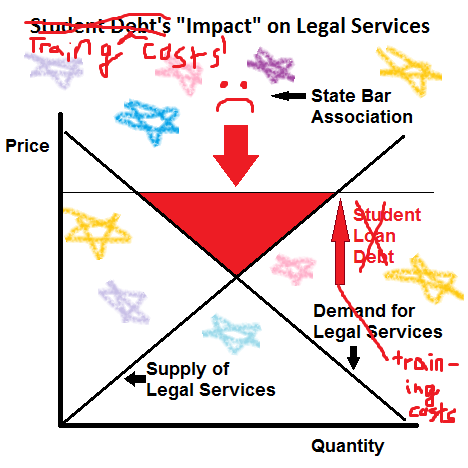

The quotations dramatize the Special Committee’s arguments effectively, but it applied good facts (I’m assuming) to bad theory. Imagine you’re a public interest firm and you have to raise your salary offers to $50,000 to attract lawyers to help them pay off their debts. This reduces the funds available to hire more attorneys, reducing the total quantity of legal services provided. Thus, it’s an indirect lawyers-pass-their-student-loans-onto-clients argument. It looks like this:

(The crayoned stars are included for illustrative clarity and because they’re cute.)

This is your garden variety price floor, the same kind that haunts minimum wage arguments. The red area that gives state bar associations frowney faces is the legal transactions, and hence, lawyer employment, that would be possible without student loan debt but are lost because of it. Remove the debt, and suddenly lawyers can happily work in low-paying jobs.

But there are at least three problems with this argument as characterized in the public interest example: (1) On page 3, the Special Committee stated that “Funding for public interest jobs is unstable,” indicating that such jobs are neither as plentiful nor as secure as the testimonials claim; (2) there are plenty of underemployed law school graduates who would love to take those kinds of jobs at $40,000 to $50,000 per year, like the solo practitioner on page 22 who made only $15,000, and we’re not told why they’re not; and (3) my criticisms of IBR notwithstanding, the Special Committee basically said that IBR doesn’t work because lawyers are scared to use it, even though for public interest lawyers the loans would be canceled after 10 years without any tax penalty. Indeed, trivializing IBR is really the only way the Special Committee could claim student debt reduces quantity of legal services.

Actually, I put up all those quotes just to show that they’re not so much evidence of student debt’s impact on the profession but are really just evidence of low demand for lawyers and low wages’ impact on the profession. In other words, even without student loan debt, these problems would still exist. No one complains that McDonald’s has low pay and high turnover—if anything, that’s built into its business model—but when lawyers dare to take higher-paying jobs than serving the poor and “middle class,” or worse, abandon their law careers, then it’s an insult to the profession. How dare they rationally choose higher-paying work? Don’t they realize that they’re lawyers?

Yes, they do realize it, but they also realize that working in law doesn’t pay very well, and they’re better off doing something else that pays more. I might be overselling this since I’m not the one gathering testimony (the new lawyers I’ve talked to have all said they’re on IBR—without reservations), but it’s unlikely that student debt is the substantial factor in lawyer underemployment here. I certainly concede that it doesn’t help.

Skills Training

I don’t want to spend too much time rehashing the argument from last week, but training costs are baked into all prices for final goods and services (i.e. not second-hand stuff). Normally, if you make the workers pay for the training—even if it’s good training—in theory they won’t pay for it if it won’t raise their incomes. The fact that lawyers’ incomes aren’t high is due to lack of demand for lawyers and the fact that some occupations might be more productive than law, not want of skills training. The theory the state bars (save New York) rely on here is identical to the one they use for student loan debt, except they’re substituting training costs with debt.

For example, returning to the California bar’s task force report:

We emphasize, above all, that we expect future improvement in practice-readiness will prepare new lawyers for the changing legal job market far better than they are today, which will help them become productive lawyers with the capacity to begin repaying educational debt at the earliest opportunity, and ultimately will lower costs to clients, who, in today’s legal market, are too often forced to bear the costs of training young lawyers, either in the form of increased fees or ineffective lawyering. (17)

Let’s think this through: If lawyers are trained well, they will be more productive, so they will serve more clients effectively than poorly trained lawyers. So far so good. It won’t necessarily reduce costs to clients, both because they’re already “forced to bear the costs of training young lawyers” and because they’d be charging market-rate prices. However, if lawyers are selling their services at the market rate, then skills training won’t raise their wages much to help them to pay off their loans, and it certainly won’t result in all law school graduates being employed as lawyers. J.D. overproduction and all that.

I add again that better training is good, but it won’t create jobs as the California, Illinois, and Massachusetts bars believe.

Poverty

I think I’ve discredited the theories the state bars are working under. Here’s mine: Demand for legal services is low during a depression and is also income elastic, meaning rich people lavish money on lawyers for the same reason that they lavish money on shiny rocks and pieces of canvas that some European splattered paint all over hundreds of years ago. Similarly, poor people spend less on lawyers because they need shelter, food, clothing, medical care, etc. more urgently. Yes, America is in fact a very poor country.

Here’s what I mean:

(Again, illustrations included for clarity.)

The red portion that gives the LSTB a frowney face is due to poor people being poor. That’s bad, and it also means they won’t hire lawyers. Note also that the slope of the line is greater than 1, which is to show that I’m theorizing that legal services are a “superior good,” which means that when income increases the quantity purchased increase more quickly. If we want poor people to afford legal services, then the state must pay for it.

Thus, in the real world, when people lose their jobs or their incomes fall due to our leave-no-rentier-behind policies, they do not hire lawyers. State bars should stop internalizing external causes of lawyer unemployment, and should admit that there are too many law schools. And if you think I’m a pessimist, then what does that make the authors of these bar reports that treat poverty as a permanent, unsolvable blight on humanity?