Certainly that’s what the IRS will tell them in 2035 when ED cancels their loan balances on IBR. Of course it won’t be real income; it’s non-negative income that they’ll never see but will have to pay income tax on nonetheless. Don’t worry though, after they wipe out their savings and take second mortgages on their houses (they will own houses, right?) they will learn the true value of higher education, to say nothing of the Social Security system they will depend on into their dotage.

This joke popped into my mind when the powers that be at the Federal Reserve opened their ecclesiastic doors and told us that six-figure student loan debt isn’t a problem and certainly not a national crisis. Not that these same folks have any credibility after ignoring an $8 trillion land bubble and their mandate to ensure full employment over price stability. That doesn’t mean they’re wrong, but it does mean we get to laugh and hurl fruit at their expensive robes.

And laugh we will, for instance, when Zero Hedge plants a FRED graph of government-held nonrevolving debt growth, and proclaims, “Please mark your calendars accordingly as yesterday [August 7, 2012] the Chairman just guaranteed that student loans will be cause for the next ‘financial stability issue.'” (Emphasis original). Funny, yes; accurate, no.

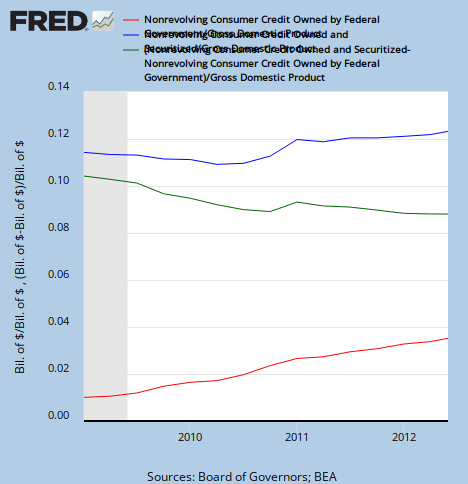

Rather, it’s ED cutting its own loans and relieving banks of their FFELP loans, which transforms them into Direct Loans. Here’s the amount of government-held nonrevolving debt to GDP (bottom), all other nonrevolving debt to GDP (middle), and all nonrevolving debt to GDP (top).

All other types of nonrevolving debt are dropping as we’d expect when everyone’s trying to pay down their debts simultaneously, but mostly it’s government debt growing and taking up a larger share of total nonrevolving debt.

So why is the government issuing and buying all these loans?

(1) Deficit reduction shell-gaming. When the government makes interest on your student loans, it “doesn’t have to raise taxes,” meaning the federal student loan program’s purpose has quietly shifted from “making college affordable” to secret, misleadingly voluntary taxes that allow politicians to avoid discussing who should actually pay for high per capita health care costs, to say nothing of all those aircraft carriers and air-conditioned tents in Afghanistan. Issuing a guaranteed loan is also a risk-free way for banks to make money—which they do—and the federal government wants in on that. Don’t worry, though. At some point in the next decade the government will tell you that the only way to bring the deficit under control is by making you pay VAT just to buy shoes.

(2) Bank bailout. If the government guarantees a loan, cancels the guarantee, and then allows the debtor to discharge the loan in bankruptcy, the bank gets hosed. The benefit of buying up the loans is it takes that risk off the banks’ books. Remember, guaranteed loans are pre-TARPed, and direct loans are Auto-TARPing in that the government bails itself out by raising taxes to cover shortfalls to its creditors, something banks can’t do.

(3) Giving borrowers better terms? Maybe, but FFELP loans have the same options as Direct Loans, e.g. they’re just as eligible for IBR.

And what of IBR, which opened this discussion? EduBubble intelligently points out that IBR socializes the debt. Not only do debtors pay taxes on their canceled debts but the revenue shortfalls must be compensated by everyone’s taxes, so debtors pay twice, once for their canceled student debts and again for others’ student debts. The latter isn’t going to be a big chunk of anyone’s tax bills, but it’ll be used as a pretext to enact poverty 1.0 taxes like VAT.

But let me soothe you: VAT is a political non-starter. Sure, Japan just doubled its VAT to 10 percent by 2015 to “reduce its deficit” (it won’t), but that country is run by masochists. In the U.S. of A., the nation’s elderly will descend on Washington like unpaid mercenaries if it tries to do something so stupid as make them pay sales taxes on their Social Security benefits. No, I suspect that by 2025 or so political gridlock caused by the taxes-on-rich-people-are-the-second-evilest-thing-in-the-history-of-evil caucus will cause our friends at the Fed to finally monetize the debt by printing money, which the taxes-on-rich-people-are-the-second-evilest-thing-in-the-history-of-evil caucus considers the evilest thing in the history of evil. Heckuva job evil-haters.

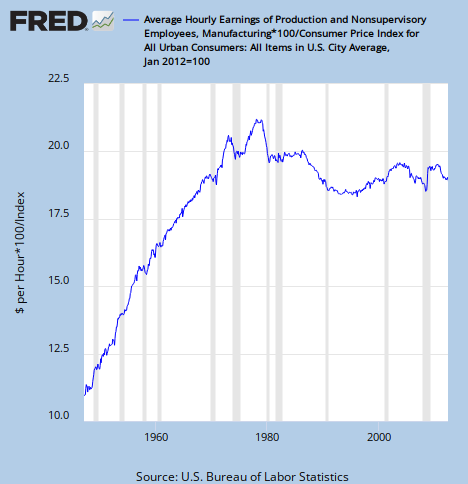

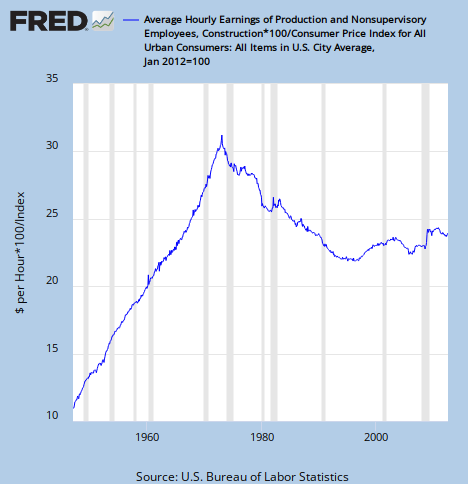

This comes as good news for our class of 2015 law grads, for the inflation will erode their debts, and they’re going to need it because almost paradoxically one of the biggest engines of inflation (the reduction of purchasing power of goods and services for the same nominal currency) is wage inflation (the reduction of purchasing power of labor for the same nominal currency). Given that we now live in the era of perpetual McJobs, here’s the hourly wage for three possible categories for underemployed law grads: retail, manufacturing, and construction over the years (2012 $).

Average Hourly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees: Retail Trade

Average Hourly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees: Manufacturing

Average Hourly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees: Manufacturing

So what’s $20.00/hour worth? In full-time annual salaries that’s $41,600. Naturally, this excludes income taxes, payroll taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, health care taxes, rents to landowners, rents to intellectual property holders, costs for subsidizing imports, student loan payments, pollution costs, commuting costs, and global warming costs.

Where does this leave our folks who don’t see student debt as a crisis? Aside from Chairman Bernanke, we have two contributions: Eric Kelderman, “Student Debt Is Growing but Is Not a National Crisis, Speakers Say,” Chronicle of Higher Education, and Tyler Kingkade, “Six-Figure Student Loan Debt Reviewed in Study by Mark Kantrowitz, Showing Rapid Growth in Past Decade,” Huffington Post.

Starting with Kantrowitz:

“[News articles about students graduating with six-figure debt levels] have shock value and sensationalize the student debt problem, but the borrowers depicted in these stories are not representative of typical college graduates,” Kantrowitz writes, going on to add “Nevertheless, much can be learned by examining extreme examples. Extrema can help identify the strengths and weaknesses of the student loan system.”

In an amusing note he tucks in his paper, Kantrowitz acknowledges that he’s only talking about people who graduate with $100,000+, not people who have that amount. He does, however, have the decency to advocate for allowing the discharge of student loans, but that’s as far as he’s willing to go because arguing that the Direct Loan Program is probably doing more harm than good means arguing himself out of a job. Can’t have that. It’s much easier to wag fingers at families and say it’s their fault the government has given up on creating living wage jobs for young people and offers them a higher education system that essentially requires students to “buy” their jobs with time and debt dollars. A hundred years ago they called this “graft”; today, they call it “getting ahead,” or “upward mobility.”

The senior economist for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, whom the Chronicle reports on, Kelly D. Edmiston, is equally unhelpful.

“The typical student borrower is not in crisis,” … [T]he median student debt—the middle range for all borrowers—is less than $14,000 … The average student debt is significantly higher, at more than $24,000, due to the 25 percent of borrowers who owe at least $30,000 for their college education. Still, another quarter of student borrowers owe less than $6,000, Mr. Edmiston found, and less than 3 percent have debt exceeding $100,000.

Elsewhere I think Edmiston misses the meaning of the default rates, as more careful Fed economists analyzed earlier this year, but the point is how the dialogue has now played out since it began a couple years ago.

Debtors and Friends: “Unpayable debt and underemployment suck hosewater.”

Establishment: “…”

Debtors and Friends: “Really, unpayable debt and underemployment suck hosewater.”

Establishment: “…”

Debtors and Friends: “Do we have to set up tents in parks? Unpayable debt and underemployment suck hosewater.”

Media: “These people have lots of debts, some graduate with more than six-figures into glutted labor markets.”

Establishment: “Hm. Let’s see. Ah, according to my research only a few of you have an arbitrarily high amount of debt (say $100,000+) and since that won’t topple the economy—not that we have any credibility predicting that—we can ignore you. You’re all ants in a glass case as far as we’re concerned.”

Liberal Establishment: “Most of you will pay those loans back anyway, and we don’t care if that reduces your standard of living compared to earlier generations. Some jobs and a little wage inflation will solve all your problems. The real problem is people with large amounts of underwater mortgages, even though they can simply mail their house keys to the mortgagees and discharge the deficiencies in Chapter 7. You need to make better arguments.”

Three responses:

(1) As Michael Hudson says, Debts that cannot be repaid, will not be repaid. Our 2015 grads will not repay their debts, IBR or no. Nor does it matter if it’s 30 million debtors or just one million. If the debts can’t be repaid, that’s a problem. I may not write about (or even think a lot about) prison abuse or drone strikes, but that doesn’t mean that I lack the compassion to form political opinions about the victims when I do read about them. It’s one thing to say that we as individuals don’t have the bandwidth to care about every single problem in the world equally; it’s another to say that because one problem is small compared to others, we don’t have to care about those suffering from it.

(2) No, student debt isn’t exactly like the housing bubble, but that doesn’t settle the issue. If the Great Depression was like a spinal fracture, and the housing bust a femur fracture, then student debt is like anemia. Defaults, negative amortization, accounting shortfalls, IBR cancellations, overpriced educations, credential inflation, and opportunity costs of schooling will sap the economy’s strength if nothing is done. This is the benefit to the government of Auto-TARPing the loans: the losses are hidden.

(3) Remember whom you are dealing with. Student debtors are an easy constituency to mobilize, and they are no less sympathetic to others who are suffering, e.g. underwater homeowners. Alienating them with condescension leaves political capital on the table for others to use. Like extremists.

The takeaway for our 2015 law grads is that the Establishment has spoken: Until the Monetary Miracle of ’25 and IBR cancellation of ’35, you will be an “extrema” for arrogant social scientists’ curiosity. Expect low wages and even less sympathy from the public. You are on your own.