…Or he deliberately misled Bloomberg‘s Lee Pacchia in an interview you can view courtesy of TaxProf Blog‘s “Case Western Dean: There Is No Oversupply of Lawyers.”

Dean Mitchell wishes to continue discussing law schools despite the poor reception of his November 2012 New York Times op-ed. Although early on he jokes that people accused him of kidnapping the Lindbergh baby, I think a line he gives at 13:33 reveals more about his perception of the debate:

One of the things the ‘Attack on Law Schools’—if I may call it that—disregards, or doesn’t assume, is that we’re working hard in good faith. You’re talking about people who, all of whom have significant opportunity costs that have gone into this business for the sake of trying to do something good.

In my opinion, bad faith doesn’t require cynically lying to make money, but defending the legal education system by raising discredited arguments, ignoring contradictory evidence, and filling knowledge gaps with conjecture qualify. Reasonable people might disagree with that definition, but I think what Dean Mitchell said in the interview, to say nothing of his selective use of Occupational Outlook Handbook information in his op-ed, suffices.

For example, Dean Mitchell peppers the interview with characterizations of law school graduates as lazy, greedy, and entitled. Thirty-eight percent of Case Western’s graduates are underemployed? It’s because they left Ohio for other cities. It’s because they won’t take lower-paying government jobs. It’s because they refuse to start small practices in the sticks. It’s because they aren’t interested in serving the poor. Then Dean Mitchell whirls around and says everything is fine: Data nine months from graduation don’t tell us of all the success stories one-year or a year-and-a-half out; law is a 40-to-50-year career so it’s premature to say the system is failing; hearsay from the admissions staff says we should be “confident” about graduates’ outcomes.

Instead of spending this post on the oversupply problem (to which I’ll only add that Pacchia discussed only new jobs and didn’t include replacements, which makes the ratio 400,000 to 212,000, not 74,000), I’m more interested in the dean’s discussion of why tuition has gone up, which I’ll present reverse-chronologically from the interview. Pacchia asks (4:35):

When we talk to people about these issues, we keep going back to the fact that tuition growth has outstripped job growth, or wage growth over the past almost two decades at a torrid pace. Why does the cost of law school tuition keep going up?

And Dean Mitchell answers:

That’s a question that any responsible law school administrator thinks about all the time. First, I point out that at my school, 20 percent of my revenue comes from our endowment, so- and believe me when I’ve spent my budget there’s nothing left. So it’s not even that our students are paying the full amount of their education. In fact, every student is subsidized to the tune of at least 20 percent simply from the income on endowment.

Where does the high price come from? Well, you know, I was looking- thinking about the ’85 to 2011 increase is often cited as being the number to look at. And medical school at 63 percent, for example. In 1985 medical school cost four times what law school cost. Also in 1985—or within a couple of years thereafter—you have a tremendous growth in starting salaries of law firms on Wall Street. Now almost anybody who teaches law could or did have one of those law jobs. I pay my faculty probably median about what the starting salary on Wall Street is. You’ve got to pay talented people to be professors, so that’s certainly one reason for the increase.

Additionally, we pay the bills like everybody else. We’ve got to pay for heating, we’ve got to pay for lighting, and we’ve developed programs for example: clinics and experiential education have exploded. That’s a very expensive form of education. You have a highly paid teacher, or a relatively highly paid teacher, teaching very small numbers of students. So when people talk about law schools as traditional cash cows, they’re imagining a time when you teach 150 kids in a class. You have a relatively small faculty doing it. You are able to charge whatever the market bore of course, but you turn a big chunk of it over to the university. I don’t turn a big chunk to the university, and I’m not teaching 150 kids in each class. So as the demands for higher quality education have increased, and as we’ve responded to that with smaller class sizes, with more skills programs, with more- other kinds of experiential endeavors, with more externships, we increase the costs.

I’m willing to grant Dean Mitchell the third paragraph, but the first paragraph is a non-sequitur. Debt is debt; underemployment is underemployment. The endowment isn’t relevant to either. The second paragraph, however, is just plain inaccurate—and not just because Pacchia said wages haven’t kept up while the dean says they grew tremendously. From the Digest of Education Statistics Table 348, we find that medical school didn’t cost quadruple law school, and law school’s costs have increased more rapidly since 1988 (close enough to 1985).

Moreover, the effective hourly wage for law professors is significantly higher than it is for first-year associates, and there are always plenty of people applying for law professor jobs who would gladly work for less pay and more classes. This is the weak link in Dean Mitchell’s response: Why does a law school need “talented people” to be professors? Can’t mediocrity get students past a bar exam?

Yes, but it won’t help Case Western win the zero-sum rankings dog-pile, and Dean Mitchell neglected to point out how tuition dollars also go to scholarships to attract high-caliber applicants, even though he acknowledges scholarships in the previous exchange (2:30):

Pacchia:

That said, the economics of the situation are troubling. Case Western, like many schools charges over $40,000 a year in tuition—I think it’s 42—yet six months after graduation, your institution had 38 percent of the class of 2011 that were either unemployed, underemployed—that is in short-term jobs or part-time jobs—or going on to get another degree. Aren’t too many of your graduates finding themselves in a position where they’re leaving school with enormous debts yet no real means to pay them off?

Dean Mitchell:

This is certainly a- debt is a problem, high tuition is a problem. I should point out that 90 percent of my class receives financial aid at a mean financial aid offer of $25,000 a year. So, people talk about the sticker prices of law schools, but we discount fairly heavily. Now, that’s not to say there aren’t students paying full freight, or there are students paying most of the way, and it’s very, very expensive. And of course, it’s important that they get jobs that they can ultimately pay that debt back, with the proceeds from, the income from.

At the same time, when you look at that 38 percent, you’re looking at a nine month picture out. Now first place, the ABA has been refining reporting statistics, along with NALP. We are- we have from the very first tried our very best to be as transparent as we can. And if you look at some of the situations of some of those students, many of them are in- you say “underemployed.” They’re in volunteer positions; they’re in positions where they receive small stipends. A school like ours, about 65 percent of our students leave the state of Ohio and go to major cities where because they’re not in law school there, it takes them more time to find jobs. I haven’t myself taken a snapshot a year out, but from- I’ve talked to my admissions staff a lot, and I suspect if you look a year out, things would change dramatically. I’m really confident if you looked a year-and-a-half out, they would.

Notice how Dean Mitchell abruptly switches from people paying full freight to minimizing the underemployment problem? Pacchia lacks my awesome powers of time travel (maybe he should drop acid before his interviews?), but the follow-up question is, where does the law school get the money to pay for scholarships for 90 percent of the students? Who is paying full freight?

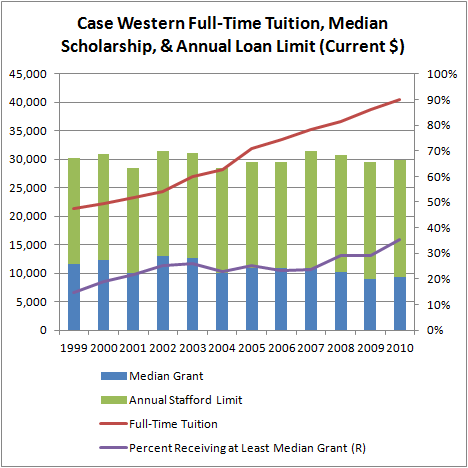

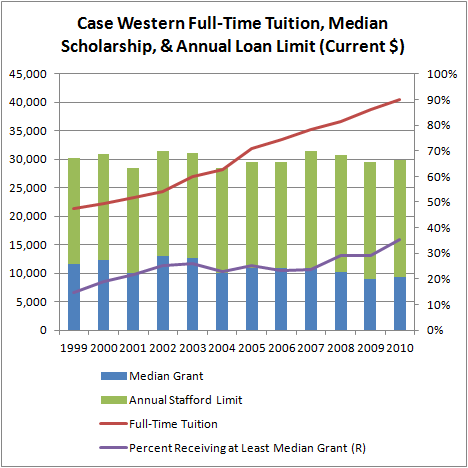

Using 12 years’ worth of Official Guide data—which Pacchia definitely wouldn’t have no matter how much acid he dropped—here’s how Case Western’s scholarship structure has transformed since 1999 for full-time students (it only has a few part-timers):

According to Dean Mitchell, the red “No Grant” blob has now contracted to 10 percent, one-third what it was even in 2010-11. Unless the law school received either a massive grant or an enormous bequest (and they didn’t blow it on a swank building), all these <50 percent tuition scholarships had to come from tuition:

Note how the median grant is now actually less in both nominal dollars and percent of total tuition than it was in 1999. The good news for the 15 percent of students who received at least the median grant back then is that their Stafford loans more than covered the shortfall. Today that’s not possible, meaning that even those who receive the median grant will have to take out a Grad PLUS loan, a private loan, or get the money from somewhere else. If we look at the glass-half-empty version, i.e. the percent of full-time Case Western students who receive the median grant or less, we find that they pay an increasing portion of whatever’s left:

Sixty-five percent of its 2010-11 full-time students had to cover 25-50 percent of their tuition with something other than Staffords. Thirty percent had to cover half their tuition outside of Staffords when in 1999 they were only down five percent. I wish the Official Guide were more forthcoming about how many 1Ls receive scholarships out of the total, but common sense tells us that it’s a high proportion, and even those who retain their scholarships after their first year will have to eat the next tuition increase to pay for … more scholarships for 1Ls. The system has evolved from one in which a handful of students receive generous portions to one in which most students get a few thousand bucks thrown their way, but it’s spread more thinly each year. Case Western does not have a tuition guarantee program.

This absurdity is only sustainable so long as there are students willing to pay ever increasing amounts of money to entice handsomer applicants than themselves to Case Western. Dean Mitchell doesn’t know or withheld that the students who pay full freight, near full freight, and every tuition increase in between are the law school’s bulwark against a rankings slide, even if there’s a high probability those graduates won’t be able to repay their loans without IBR/ICR or miracling high-paying jobs. These students’ continued access to unlimited federal students loans is the sine qua non of Case Western’s financial model.

Pacchia didn’t pursue this line of questioning, but file it away for the next time a law school dean wants to have a “good faith” dialogue about the non-crisis entitled law graduates face.