Discussions of law-school costs are incomplete if they do not include discounts some students receive, usually as merit scholarships paid for by their full-tuition-paying classmates. The topic is salient today because Congress is considering limiting the amount law students can borrow from the federal government. If the PROSPER Act passes, then it’s likely law schools would need to reorganize their cost structures—notably by reducing scholarships and their full price tags. To analyze the phenomenon of discounting, I focus on the ABA’s 509 information reports’ scholarship data. This information lags the academic year by one year, so as of the 2017-18 academic year, we now have data on 2016-17. One new drawback this year is that law schools that closed or stopped accepting new students before 2017 did not provide scholarship data for 2016, so the picture is slightly distorted.

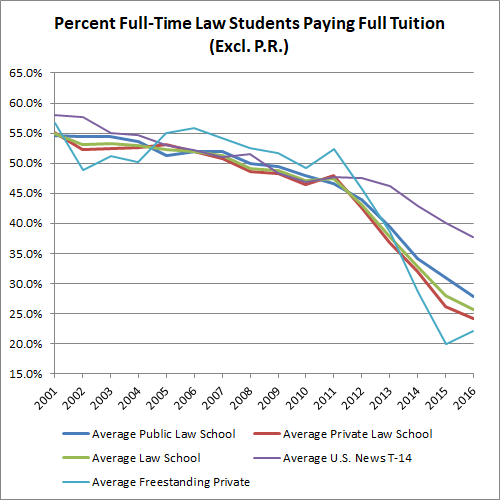

In 2016, the proportion of full-time students paying full tuition fell by 2.4 percentage points from 28.1 percent to 25.7 percent at the average law school not in Puerto Rico. At the median law school less than one-quarter of students pay full tuition.

The proportion of students paying full tuition has fallen considerably over the years. At the turn of the century, more than half of students paid full cost; now about a quarter do.

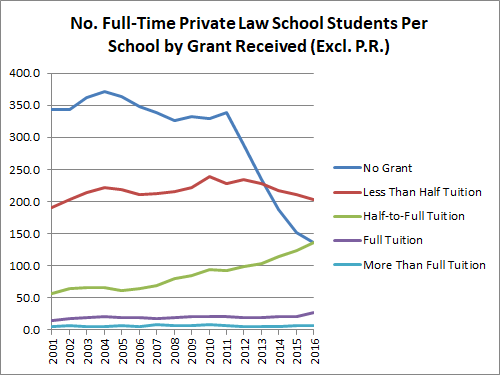

At the average private law school, which don’t price discriminate in favor of resident students, the number of students receiving grants ranging between half tuition and full tuition now exceeds the number paying full tuition. Many more receive a grant worth less-than-half tuition.

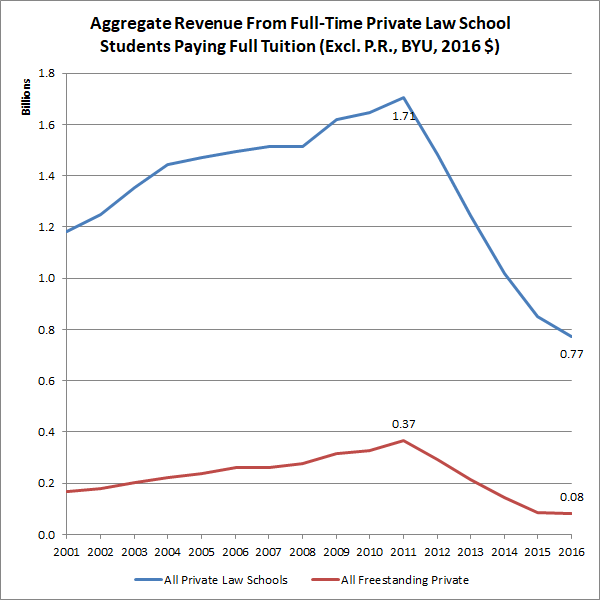

One advantage of knowing how many full-time students pay full tuition is that we can estimate the total revenue they generate for private law schools, except Brigham Young University, which charges LDS students less.

Since 2011, the peak year, inflation-adjusted revenue from full-tuition-paying full-time students has fallen 55 percent. Since 2001, the last year for which data are available, the drop is 35 percent. In 2016, the median private law school’s full-tuition revenue was $3.8 million, down from $12.2 million in 2011. In 2001, the median was $9 million. This is quite a precipitous decline.

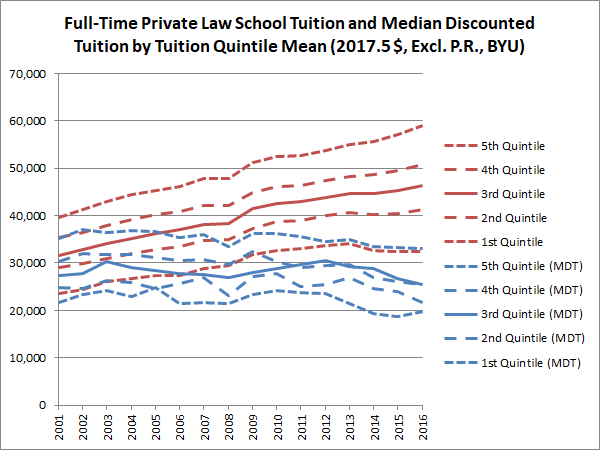

So how substantially are private law schools discounting? The best way to answer that question is by treating the sticker price at private law schools as the independent variable, and treating as the dependent variable their tuition after subtracting their median grant (median-discounted tuition “MDT”). First I divide private law schools into full tuition quintiles and give their mean averages. Then I take mean of the MDTs within each quintile.

We find that the MDT at the most expensive law schools is about as much as full tuition at the cheapest private law schools. Meanwhile, schools in the fourth quintile now discount to the level that third quintile law schools do. This indicates pretty fierce competition for students. MDTs at the bottom four-fifths of law schools are converging with one another while diverging from the most expensive schools.

That’s all for now.

Information on this topic from previous years:

- “2015: Full-Time Law Students Paying Full Tuition Fell ~5 Percentage Points (Again)” (January 11, 2017)

- “Full-Time Students Paying Full Tuition Fell ~5 Percentage Points in 2014” (January 4, 2016)

3 comments