[The following post first appeared on this site on January 1, 2012. What it said then still applies today, mutatis mutandis. Thanks for reading the blog and have a prosperous 2021!]

Behold, the curse of a long memory. Last January [2011], Google Alerts sent me an e-mail informing me that the National Inflation Association (“Preparing Americans for Hyperinflation”) issued a press release predicting that the higher ed bubble was “set to burst beginning in mid-2011. This bursting bubble will have effects that are even more far-reaching than the bursting of the Real Estate bubble in 2006.” The NIA press release then digressed into legal education (I’m guessing they’d just read David Segal’s first NYT piece a few days earlier), how evil lawyers are, how they produce nothing for society, and how 60 percent of the Senate and 37 percent of the House are lawyers who rig the economy to make jobs for lawyers. It editorializes:

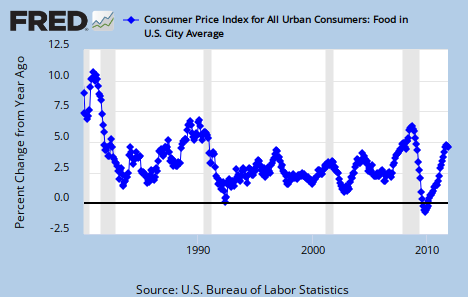

“While everybody went to school to become a lawyer [really?], nobody went to school to become a farmer because Americans didn’t see any money in farming. With prices of nearly all agricultural commodities soaring through the roof in 2010 and with NIA expecting this trend to continue throughout 2011, the few new farmers out there are going to become rich while lawyers are standing at street corners with cups begging for money.”

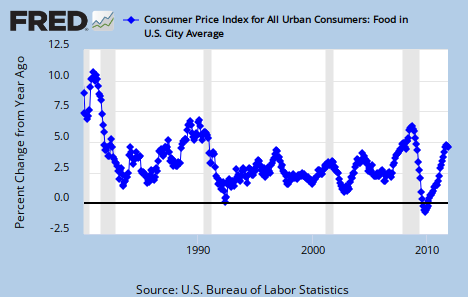

The NIA would’ve been more helpful if it explained how lawyers could be a drain on society yet remain vulnerable to market forces. Also, one would think unemployed lawyers would try to find non-lawyer jobs instead of begging, but I think it’s important to note that agricultural prices weren’t “soaring through the roof” in 2010. They were growing, yes, but although the NIA was right that they continued to do so in 2011, (a) it’s stalled recently, and (b) they’re no worse than they were in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Oh well. The NIA sternly concluded:

“We must work hard to educate America to the truth if our country is going to have the wherewithal to survive the upcoming bursting college bubble and Hyperinflationary Great Depression.”

Whoa.

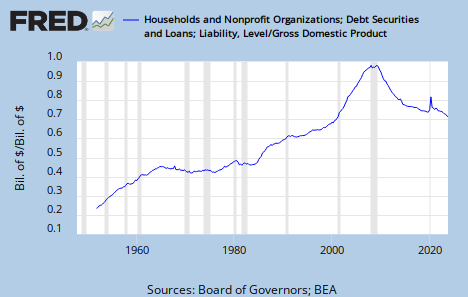

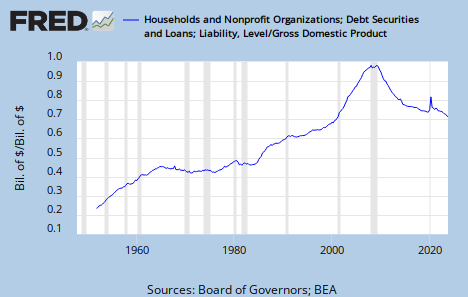

I can’t say I’m quite as disappointed as the NIA undoubtedly is that we’re not seeing much inflation these days, and in mid-2011 I didn’t see many colleges cutting their tuition, laying off faculty, closing programs, or trying to retrench themselves. I also remain unconvinced that $1 trillion in student debt can be worse than $8 trillion in mortgage debt. True, student debt is not dischargeable (unlike mortgage deficiencies) absent a showing of an undue hardship, and it’s hampering the recovery and ruining lives, but it’s not worse in quantity than the housing bubble. As for the NIA’s paranoid ranting about lawyers, all economic evidence I’ve seen indicates that legal services have all but stagnated for much of the last two decades. Apparently, those 60 percent of lawyer-senators aren’t very good at creating work for themselves. I suppose the NIA should express appreciation.

Anyway, if anything, inflation would be a boon to underwater homeowners and student debtors because it erodes the real value of their debts, which grew significantly in the 2000s. Here’s household debt to GDP:

Importantly, I’m no macroeconomist but I’ve never heard of a “hyperinflationary depression.” The terms contradict each other. Depressions occur when people take on excessive debt and begin paying it down simultaneously instead of spending money on other things. This is deflationary because new credit isn’t being created, even by the government. By contrast, hyperinflation has only occurred in unusual circumstances, like when a government owes debts to foreigners in a different currency. Weimar Germany, for example, owed gold-dominated war reparations to the Allied powers, and to purchase the gold, it printed money, causing hyperinflation. Zimbabwe isn’t a good comparison either because it’s a small, HIV-ridden landlocked state with an undiversified, oligopolistic agrarian economy while the U.S. is a wealthy, continent-spanning super-state.

As for inflation fears generally, maybe it’s the fact that I have no memory of high inflation, but why isn’t there a “National Personal Income Association” (NPIA) that regularly celebrates increases in Americans’ per capita personal income?

“Per capita personal income has quadrupled since 1980! Prices didn’t even triple! Hooray! We’re rich! Fiat currency forever and ever! ‘You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!'”

I’m sure the NPIA wouldn’t’ve been too thrilled with 2008-09, but personal income is increasing again. The problem has just been that over the decades those gains haven’t been distributed equally. This isn’t a problem of inflation but one of wages and taxation.

Intuition tells me the NIA won’t spend early 2012 carefully discussing why the higher ed bubble didn’t burst in mid-2011 as it predicted, nor will it take the time to explain why Americans—many of whom are net debtors—should be concerned about inflation. Instead it will prophecy even more hyperinflation later. But here’s hoping the National Inflation Association won’t provide me entertainment come January 1, 2013. Such is the curse of a long memory.