“The moral case for doing a better job of giving Americans the opportunity to succeed is very compelling. The economic case is just as strong. If more Americans are educated, more will be employed, their collective earnings will be greater, and the overall productivity of the American workforce will be higher.” –Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, March 15, 2012 (13)

Jan Eberly and Carmel Martin, “The Economic Case for Higher Education,” (more neutrally titled “The Economics of Higher Education” in the actual PDF) Treasury Notes.

Eberly is the Assistant Secretary for Economic Policy and Chief Economist for the Department of the Treasury, and Martin is the Assistant Secretary for Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development for the Department of Education (or at least those were their positions in the previous administration). Yes, you read the title right: Even the Treasury Department thinks sending everyone to college is nonnegotiable because it’s absolutely impossible to create living wage jobs otherwise. I come down hard on this perspective not just because it’s wrong, and not just pessimistically so, but because this was the government that ran on “hope and change” that now says there’s no hope and only cosmetic changes in student loan repayment plans.

As I dive into the paper itself, keep this question in your mind: Why would Treasury and ED join forces (TreasurED?) to craft the same post hoc ergo propter hoc argument defending unlimited higher education that everyone else is fond of?

.

.

.

While you were chewing on that, I read this line in the fact sheet, which doesn’t appear in the actual paper:

Workers with more than a bachelor’s degree see an even wider gap relative to high school graduates on average. For example, a worker with a master’s degree typically earned twice as much in 2011 as one with a high school diploma. Those with a professional degree, such as a J.D., earned more than two-and-a-half times as much on average.

Why? Why in the name of Lord Xenu bring up law degrees? Why?? It’s a casual reference, but the Treasury Department is joining discredited composition fallacizers as the Pew Research Center and the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, and for even this minor an infraction I can give “The Economic Case for Higher Education” no quarter.

The odious line about law degrees refers to this terribly misleading graphic from the BLS:

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (2012). Data are for individuals age 25 and over. Earnings are for full-time wage and salary workers.

Real translation: Education pays off, when it pays off, if it pays off.

Long form: When your earnings are at or above the median, and if you have a full-time wage-and-salary job, then you will earn 2.6 times as much or more than the median high school-educated worker who also has a full-time wage-and-salary job. If, for example, you are self-employed, your earnings are not counted. If you are working part-time, your earnings are not counted. If you are ass-unemployed, your $0 weekly earnings are uncounted. It is fully possible that your degree is in no way necessary for your full-time wage-and-salary job, and in the end of all things it is fully possible that your degree’s substantive coursework in no way prepared you for your job’s duties, and its value is wholly due to the signal it sends to employers. Welcome to the world of credential inflation: Population: Untold Millions.

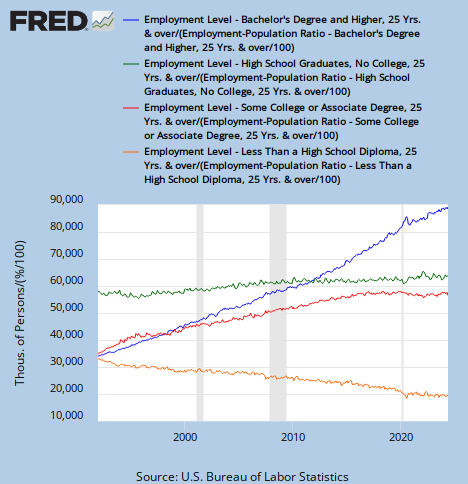

Credential inflation also muddies the usefulness of the left side of the chart that connects higher education and low unemployment for just about all the reasons I listed above plus the fact that the unemployment rates are all measured with different civilian-labor-force-level denominators. Here’s what they have looked like since 1992.

(Blue = “Bachelor’s Degree or Greater,” Red = “Some College or Associate Degree,” Green = “High School Graduates, No College,” Red/Green = “Less than a High School Diploma.”)

Here’s the unemployment level, the numerator:

To be sure, the percent of unemployed less-than-high-schoolers is higher than the others, but in absolute terms, it’s the smallest unemployed category. I’m also willing to bet that a lot of them didn’t grow up here and don’t know English very well, i.e. people who come here because they are willing to work for low wages.

Let me also draw your attention to the absurd “Some College or Associate Degree” category, for no one else seems to consider it. Even when you include people who get two-year degrees, those in this category barely make more than those who finish high school. In other words, the college premium is back-loaded: you only get the benefits if you get the diploma (when/if you’re employed full-time, etc.). This is consistent with credential inflation, otherwise people would leave college once they had completed the minimum number of classes to qualify them for the work they’re doing, receive a more significant earnings boost, and probably be no less likely to be unemployed than those who finished a four-year degree.

Incidentally, in footnote 21, Eberly and Martin write, “In Q1 2012, BLS estimated that approximately 26 million individuals age 25 and older have some college or an associate’s degree; another 35 million have at least a four-year degree.” Um, no. It’s like double that.

There are now more Americans over 25 (60 million+) who have at least a four-year degree than who only have a high school degree. The number who have an Associate’s degree or some college is closing on the number of high schoolers, but they too number over 50 million. Don’t let that fool you though: A lot of these people aren’t in the labor force anymore.

Skill Premium

One American in three has some tertiary education. Why is it not enough? Answer: the college “skill premium.”

Empirical evidence suggests that one important driver of the rising skill premium is the continually increasing demand for skilled workers and a deceleration in the supply of college graduates.24 Since at least the early 20th Century, technology has allowed advanced economies to substitute physical capital for manual labor in the production of goods and services. Machinery, computers, and other technical infrastructure have required skilled workers to design and operate; this so-called “skill-biased technological change” increased the relative demand for skilled workers.25 While demand for skilled labor has continually increased, the supply of college-educated workers has not kept pace. The 1960s and 1970s were associated with an increase in college attendance, leading to a rapid influx of skilled workers into the labor force in the 1970s, and thus decreasing the skill premium in that period. However, the relative supply of college-educated workers has slowed since the 1980s, which further magnified the increases in the skill premium (see panel B in Figure 5).26 (14-15)

In other words, college is where people learn to use computers by typing up long papers (or where they learn to unscrupulously buy them off the Internet).

David Autor’s 2010 paper on job polarization (PDF) is the basis for the report’s skill premium argument, and I have to credit Eberly and Martin for condensing him so succinctly, as his paper is not so clear. I admit I’ve never heard anyone say that the deceleration in degree-conferring has caused wage polarization between college-educated and high school-educated workers, but it’s still unpersuasive. Here’s Autor’s reasoning with some of the gaps filled in by me:

(1) Demand for high-skill jobs is increasing due to “skill-biased technological change” and the “competitive global economy.”

(2) The rate of increase in the supply of high-skill workers is decelerating.

(3) As a result, high-skill workers’ wages are separating from low-skill workers’ wages.

(4) (Low-skill workers’ wages are dropping for other reasons too, e.g. union-busting and off-shoring, but it’s absolutely impossible to raise wages for low-skill workers.)

(5) (College education is the only way to beat skill-biased technological change.)

(6) (All high-skill workers are equally fungible, i.e. course of study doesn’t matter.)

(7) The solution is to increase the supply of high-skill workers to fill the wage gap and … reduce their expected wages. Yes. Severely reduced pay for all.

The biggest fault here is in proposition one. Plenty of people in the U.S. have disproportionately high earnings for reasons other than mastering the “vlookup” function in MS Excel. Examples abound: Bain Capital’s principals’ fortunes came about essentially by bankruptcy fraud; three Wall Street executives were convicted over a massive nationwide bid-rigging scam of municipal bond markets; and the tax code leaves all kinds of unearned incomes untouched, like patents, copyrights, and land rents. The dream of meritocracy conceals the reality of kleptocracy.

To Be Continued…